The following was written for the ‘Whatever happened to the MOOC?‘ panel session on 12th March 2014 at the Jisc Digifest. I was given 5 minutes to take the story from Open Learning has a past to the next contribution from Jonathan Worth on the open courses at Coventry.

As soon as ancient civilisations began to record, collate and preserve their knowledge, inequalities emerged. ‘Experts’ owned and controlled that knowledge in specialised collections and academies of various kinds, often connected to religious teaching.

There has always been a dilemma in educating societies, because educated masses are dangerous and can challenge the order of the day. So you could argue that formal education has always been about ownership and control of information, learning and knowledge. And so the struggle to make education accessible to all began…

A struggle against restrictive practices in curriculum design, closed collections, selective entrance, expensive technologies and equipment, accreditation led learning, exclusive language and the impact of poverty and exclusion – all these things which we might not expect to see in a world of inclusive open education….

Paulo Friere said in his 1970 publication Pedagogy of the Oppressed

“Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity or it becomes the practice of freedom, the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world.”

So how far have we actually come?

Online networking and information technologies have had the potential to transform accessibility to learning and how we design and develop educational opportunities. This has been fraught with challenges around changing cultures of academic practice, established traditions within educational institutions, legal restrictions around ownership and control of content, restrictive publisher practices, challenging existing communities of practice, changing learner expectations, government strategies and policies.

Many of us have been working to overcome these challenges for many years and we have had some successes in, for example, improving services to distance learning students and also in supporting students with learning disabilities. But did this really help address inequalities and widen participation in a broader sense?

Alongside the development of online technologies has been the growth of the open education movement – so for example in 1971 the UK Open University enrolled its first students and aimed to improve access to post-secondary education through it’s distance learning materials and BBC broadcasts. So if you had a TV and could afford a TV licence, if you had the means to pay for a course and the level of understanding to learn from those materials this had the potential to change lives and it has for lots of people… In 2006 the OU developed OpenLearn making learning materials freely available to download and adapt for re-use by anyone worldwide who has the means to access the web, and the capacity to learn in this way.

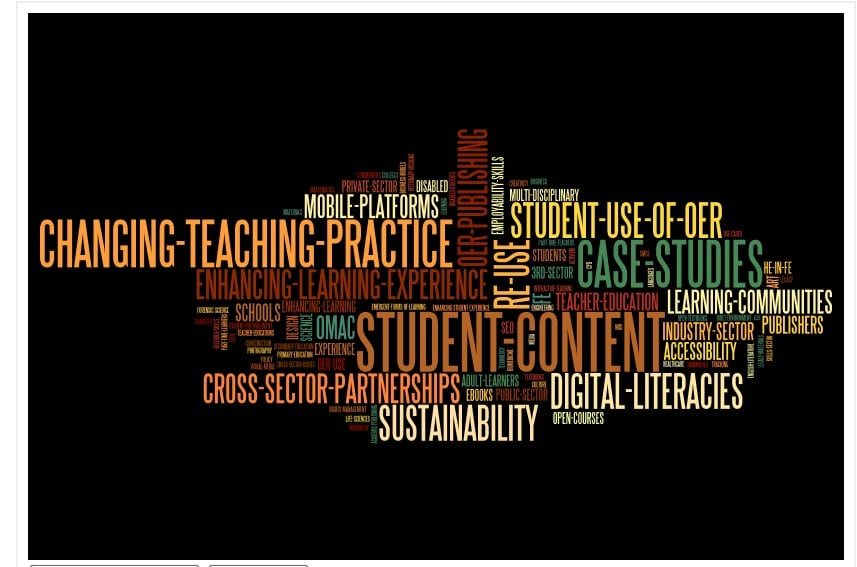

This timeline developed for Cetis highlights various national and international initiatives that have moved us forward in terms of Open Education, including MIT Courseware (2001), Jisc Exchange for Learning Programme (2002-2006), Jorum National Learning Repository (2002), Creative Commons (2002), U-NOW Nottingham University (2007), Jisc RePRODUCE Programme (2008), First MOOC (2008), UKOER Programme (2009-2012) http://blogs.cetis.ac.uk/othervoices/2012/02/13/open-educational-resources-timeline/

Open Educational practices

Have we really transformed how we support learning through these new technologies and new approaches or have we just used them to support the traditional ways in which ‘experts transmit’ knowledge… Can we really transform the way we provide accreditation without challenging the whole infrastructure that supports our prevalent education systems. Do we want to or would that just be too challenging to really open up learning. There has been a tendency to focus on learning resources rather than enabling people to learn effectively in an open, networked social world.

The recent 3 year UKOER Programme supported individuals, communities and institutions to experiment with making learning materials open and saw evidence of new emerging open pedagogies where students were co-producers of adaptable open learning materials and active participants in new open learning networks. Other stakeholders became involved in producing and using learning materials – from commercial publishers, trade associations, schools, to professionals in the field. Traditional roles and boundaries were really challenged at all levels of the institutions. Curricula were redesigned, and in some cases transformed by involving students in new open approaches to creating, curating and sharing content, and participating in authentic learning situations.

The open education movement has a specific focus on making educational materials freely available to all in a global sense. From the MIT Courseware initiative to the large scale MOOCs there is no lack of high profile initiatives. So is the open education movement today a manifestation of the struggle against restrictive practices? For many it probably is – the altruistic desire to make opportunities for learning accessible to all. But this is not the only motivation and the complexities behind the wide range of motivations has led to some tensions. Open Educational Resources and Open Learning Courses are not free – they represent a significant financial investment, and as such they often support the visions, strategies and values of the persons, communities, or institutions making that investment. In fact they are often created or developed for very specific groups of people making their true pedagogic accessibility limited…

How far is it possible to break down those barriers of ownership and control… one of the best examples has to be the development and widescale adoption of creative commons licences – they reveal a massive commitment to making learning materials more open, adaptable and re-usable. But sometimes it’s the more subtle barriers that thwart openness.

Not all open courses have taken account of the lessons we have learned over the years or utilised the open resources we’ve created, but there are some open courses that really have challenged traditional aspects of ownesrhip and control. Some particulary powerful examples are the Open Media Courses at the University of Coventry which have broken down some of the barriers and gives us a real taste of how different open education can be.

Look out for a chapter in an upcoming book Littlejohn, A., Falconer, I., McGill, L. & Beetham, H. (2014) Open Lifewide Learning: a vision, Chapter 8, Reusing Open Resources, Routledge, London: NY, Littlejohn, A.& Pegler, C. (Eds)

Leave A Comment